As of March 2024, astronomers have discovered nine new binary cepheid systems, including one in the Milky Way and others in the Small and Large Magellanic Cloud. The closest binary cepheid system is 11 kiloparsecs (about 3,000 light-years) away in the Milky Way

Cepheid variables are stars that change brightness regularly, which is useful for astronomy because astronomers can measure distance to a Cepheid by measuring the variability of its luminosity. Cepheids are especially powerful stars that are found in binary systems, and about one-third of Galactic Cepheids are known to have companions

The first Cepheid variable star, Eta Aquilae, was discovered in 1784 by Edward Pigott. The pattern of these stars pulsating in and out was first noticed in 1784 in the constellation Cepheus, which is how they got their name

In 1908, Henrietta Swan Leavitt discovered the relationship between the period and luminosity of Cepheid variables. This discovery allowed astronomers to determine the distance of Cepheids by observing their pulsation period.

Leavitt’s findings were published in 1912, and they allowed astronomers to determine the distance of Cepheids up to 10 million light years. This became a “yardstick to the universe” that Edwin Hubble and others used to make discoveries that changed our view of the universe and galaxy

This characteristic of classical Cepheids was discovered in 1908 by Henrietta Swan Leavitt after studying thousands of variable stars in the Magellanic Clouds. The discovery allows one to know the true luminosity of a Cepheid by just observing its pulsation period

Astronomers identify Cepheid variable stars by observing their radial pulsation, which results in a clear change in their luminosity. For example, a Cepheid variable star might go through a cycle of becoming very bright, then dimmer, and back to very bright again over a period of time

By observing how the star’s brightness changes, astronomers can determine its period, or the amount of time it takes for the star to complete one full cycle of pulsation. This period is directly related to the star’s luminosity. This means that the star’s distance can be easily extrapolated by comparing their predicted brightness to their apparent brightness.

Cepheid variables are extremely luminous and can be used to measure distances from about 1kpc to 50 Mpc

As of March 2024, astronomers have discovered nine new binary cepheid systems, including one in the Milky Way and others in the Small and Large Magellanic Cloud. The closest system is 11 kiloparsecs (about 3,000 light-years) away

Binary cepheid systems are laboratories for stellar evolution, and Cepheids in binary systems are especially powerful. About one-third of Galactic Cepheids are known to have companions.

Cepheid variables are a type of variable star that have relatively long periods, ranging from about 1.5 days to more than 50 days. They are found largely in the spiral arms of galaxies and are called Population I. Population II Cepheids are much older, less luminous, and less massive than Population I Cepheids.

The North Star (Polaris) is the closest Cepheid variable star to Earth, at a distance of 445.5 light-years. It is also the brightest Cepheid variable

Cepheid variables are useful for measuring interstellar and intergalactic distances because their luminosity is closely related to their period of variation. This means that if you can measure the time between two peaks in their brightness, you can use Leavitt’s Law to figure out the absolute brightness of the star.

Cepheid variables can be seen and measured out to a distance of about 20 million light years. However, Earth-based parallax measurements can only measure distances of about 65 light years, and the Hipparcos space-based instrument can only measure distances of somewhat over 100 pc (326 light years)

Polaris is not only famous as the beacon for early navigators, it is also the closest Cepheid to earth (445.5 light-years away), and a subject of intense study

Measuring the distance to far away objects in space can be tricky. We don’t even know the precise distance to even our closest neighbors in the Universe – the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds. But, we’re starting to get to the tools to measure it. One type of tool is a Cepheid Variable – a type of star that varies its luminosity in a well-defined pattern. However, we don’t know much about their physical properties, making utilizing them as distance markers harder. Finding their physical properties would be easier if there were any Cepheid binaries that we could study, but astronomers have only found one pair so far. Until a recent paper from researchers from Europe, the US, and Chile shows measurements of 9 additional binary Cepheid systems – enough that we can start understanding the statistics of these useful distance markers.

Like traditional stars, binary Cepheid systems result when two stars orbit around each other. In this case, both of those stars must be Cepheids – meaning they are massive compared to our Sun and much brighter. In addition, their luminosity must vary in a repeatable pattern so that we can track it consistently.

All of those features can vary a lot if two stars change in luminosity but at different rates and phases around each other. It’s difficult to parse out which star is waxing, which is waning, and which direction they are moving in, both compared to us and each other. Long periods of observation are required to fix some of those variables, and that is precisely what the new paper describes.

Understanding how these systems exist and where they are is just the first step. Using them for more helpful science is the next. The most obvious way to do so is to increase our understanding of Cepheids. Despite being one of the most commonly used distance markers in the Universe, we know surprisingly little about how they form, what they’re made of, or their life cycle. Closely studying a binary system, where the stars interact, could help shed light (figuratively in this sense) on some of those properties

Like traditional stars, binary Cepheid systems result when two stars orbit around each other. In this case, both of those stars must be Cepheids – meaning they are massive compared to our Sun and much brighter. In addition, their luminosity must vary in a repeatable pattern so that we can track it consistently

In March 2024, astronomers from Europe, the US, and Chile found nine new binary Cepheid systems, including two in the LMC, five in the Small Magellanic Cloud (SMC), and two in the Milky Way (MW). The systems have orbital periods ranging from 2–18 years

Using traditional methods, it’s very difficult to identify these systems in other galaxies, as it can take decades of monitoring to find a few. However, the new method of detection is independent of the orbital size, and several systems with very wide orbits have already been identified

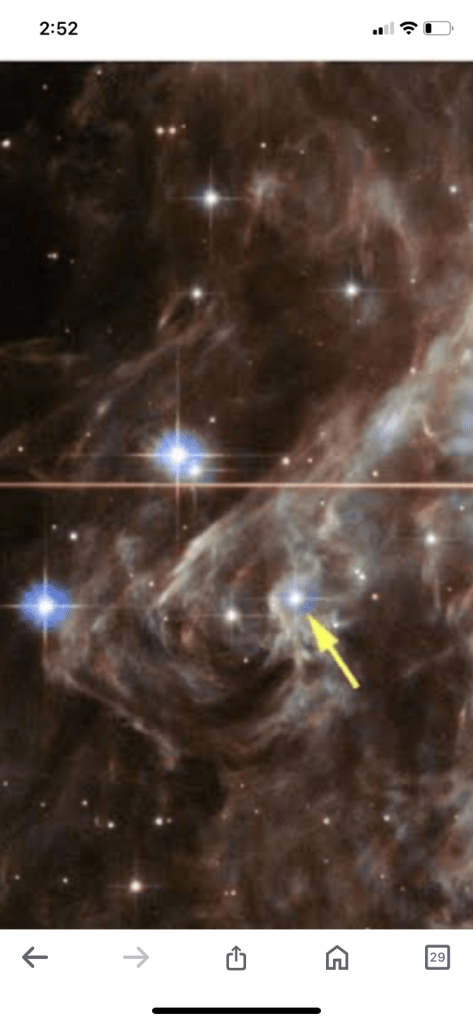

Astronomers Only Knew of a Single Binary Cepheid System. Now They Just Found Nine More – Universe Today. This Hubble image shows RS Puppis, a type of variable star known as a Cepheid variable

Please like subscribe comment your precious thoughts on universe discoveries ( a perfect destination for universe new discoveries and science discoveries)

Full article source google

https://www.amazon.in/b?_encoding=UTF8&tag=555101-21&linkCode=ur2&linkId=80fb4c3470b5df5903dc59fd3da06150&camp=3638&creative=24630&node=1983518031