Some research shows that when the planet lost its water and became totally inhabitable, there was lots of oxygen in its atmosphere. If we saw that same amount of oxygen on a distant exoplanet, we might interpret it as a sign of life

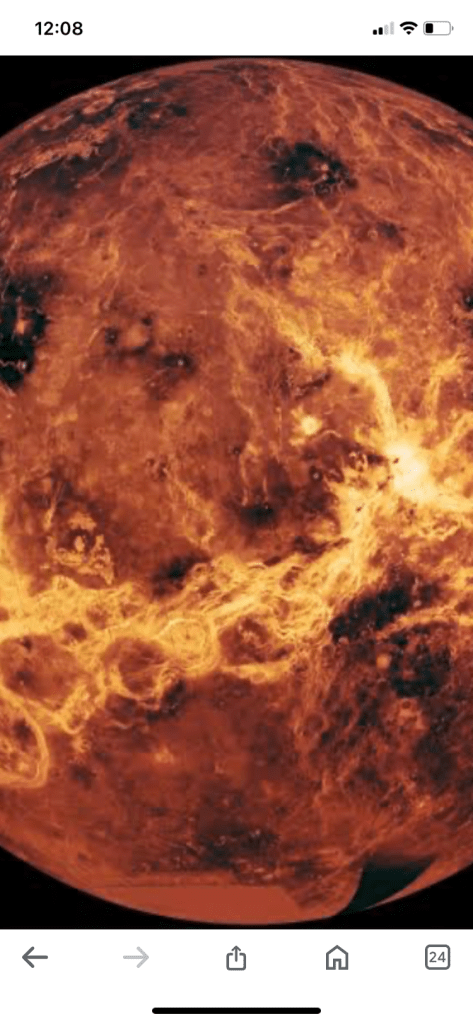

Even though Venus and Earth are so-called sister planets, they’re as different as heaven and hell. Earth is a natural paradise where life has persevered under its azure skies despite multiple mass extinctions. On the other hand, Venus is a blistering planet with clouds of sulphuric acid and atmospheric pressure strong enough to squash a human being

But the sister thing won’t go away because both worlds are about the same mass and radius and are rocky planets next to one another in the inner Solar System. Why are they so different? What do the differences tell us about our search for life?

A major focus of the planetary science and astrobiology community is understanding planetary habitability, including the myriad factors that control the evolution and sustainability of temperate surface environments such as that of Earth. The few substantial terrestrial planetary atmospheres within the Solar System serve as a critical resource for studying these habitability factors, from which models can be constructed for application to extrasolar planets. The recent astronomy and astrophysics and planetary science and astrobiology decadal surveys both emphasize the need for an improved understanding of planetary habitability as an essential goal within the context of astrobiology. The divergence in climate evolution of Venus and Earth provides a major accessible basis for understanding how the habitability of large rocky worlds evolves with time and what conditions limit the boundaries of habitability. Here we argue that Venus can be considered an ‘anchor point’ for understanding planetary habitability within the context of the evolution of terrestrial planets. We discuss the major factors that have influenced the respective evolutionary pathways of Venus and Earth, how these factors might be weighted in their overall influence and the measurements that will shed further light on their impacts on these worlds’ histories. We further discuss the importance of Venus with respect to both the recent decadal surveys and how these community consensus

reports can help shape the exploration of Venus in the coming decades.

Earth is an exception. With its temperate climate and surface water, it’s been habitable for billions of years, albeit with some climate episodes that severely restricted life. But when we look at Mars, it seems to have been habitable for a period of time and then lost its atmosphere and its surface water. Mars’ situation must be more common than Earth’s

But Venus is a challenge. We can’t see through its dense clouds except with radar, and nobody’s tried landing a spacecraft there since the USSR in the 1980s. Most of those attempts failed, and the ones that survived didn’t last long. Without better data, we can’t understand Venus’ history. The simple answer is that it’s closer to the Sun. But it’s too simple to be helpful

Despite surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead, lava-spewing volcanoes, and puffy clouds of sulfuric acid, uninhabitable Venus offers vital lessons about the potential for life on other planets, a new paper argues

We often assume that Earth is the model of habitability, but if you consider this planet in isolation, we don’t know where the boundaries and limitations are,” said UC Riverside astrophysicist and paper first author Stephen Kane. “Venus gives us that

For the study, the researchers examined the atmospheres of what are known as exoVenuses, which are exoplanets that lie within the Venus Zone (VZ), or inside the runaway greenhouse boundary of their parent star’s orbit. Astronomers hope to use exoVenus atmospheres as analogs to not only better understand the runaway greenhouse effect of Venus, but its past, as well.

“Oxygen is often considered a potential exoplanet biosignature because, on Earth today, it is almost entirely the result of photosynthetic life,” Dr. Eddie Schwieterman, who is an Assistant Professor of Astrobiology at UC Riverside and a co-author on the study, told Space.com in an email. “However, one potential abiotic way of accumulating oxygen in a planetary atmosphere is through an extended runaway greenhouse. Water is brought to the upper atmosphere and split apart by UV photons from the star, which drives the escape of the light hydrogen and retention of the heavier oxygen from that H2O.

There are other sinks for oxygen, but oxygen could build up in the atmosphere if they are exhausted. M dwarf stars, which are the first targets for planetary characterization with JWST, are super luminous early in their lives, and this super luminous phase would enhance the loss of atmosphere to space. We don’t know how common abiotic oxygen accumulation is on exoplanets, but we would expect it to be more likely on Venus Zone planets than on planets further away from their stars. If we survey Venus Zone planets, where life is unlikely, and find many with oxygen, it may caution us regarding life interpretations on temperate planets. On the other hand, if we do not find oxygen-rich Venus Zone planets, that would be a good sign for oxygen biosignatures on Earth-like worlds inside the habitable zone.”

Yes, some research suggests that when Venus lost its water and became uninhabitable, its atmosphere had a lot of oxygen. However, a report in Phys.org says that carbon and oxygen on Venus are moving so quickly that they can escape the planet’s gravity. The report also says that most of Venus’s ionosphere’s heavy ions are slow-moving and cold

Early in Venus’s history, the solar wind stripped away its water, leaving an atmosphere made up of carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and other trace species. Sunlight broke down the water in Venus’s atmosphere into hydrogen and oxygen, but the hydrogen escaped into space due to the planet’s high temperatures. This process is called hydrodynamic escape.

Researchers believe that Venus once had as much water as Earth, but a rise in greenhouse gases caused runaway temperatures that vaporized all the water, which was then lost to space

Why is Venus the deadliest planet?

0.015% 0.007% 3.5% 64% Page 2 Venus is the most dangerous planet in the solar system: its surface is at 393°C, hot enough to melt lead. It’s even hotter than the planet Mercury, which is closest to the Sun. Venus’ atmosphere is acidic and thick

What can Venus tell us about the future of Earth?

What can Venus tell us about climate change on Earth and the future of our planet? If at some point Earth gets warm enough, it will trigger a runaway greenhouse effect, which will result in oceans evaporating from the surface and into the atmosphere, and this may be irreversible

What does Venus teach us?

By studying Venus, scientists learn how Earth-like planets evolve and what conditions exist on Earth-sized exoplanets. Venus also helps scientists model Earth’s climate, and serves as a cautionary tale on how dramatically a planet’s climate can change

Please like subscribe comment your precious thoughts on universe discoveries

Full article source google

Best health books on discount on Amazon

jo Best science and mathematics books on discount on Amazon

Best science technology books on discount on Amazon