Jupiter’s four largest moons, the Galilean moons, are believed to have formed from a circumplanetary disk of gas and dust that surrounded the planet during its early formation. This is similar to how the planets of our solar system formed from the protoplanetary disk around the Sun.

The Formation Process

The leading theory suggests a multi-step process:

- Circumplanetary Disk: After Jupiter formed, leftover gas and dust from the solar nebula settled into a disk around the new giant planet. This disk acted as a “dust trap,” collecting icy grains and other materials.

- Moon “Seeds” and Accretion: Within this disk, “satellitesimals”—small, icy bodies—began to form and collide, gradually growing larger. This process, known as pebble accretion, eventually led to the creation of moon embryos.

- Sequential Formation: The moons likely formed one after another, starting with the innermost one, Io. As each moon grew, its gravitational pull created waves in the gaseous disk, causing it to migrate inward toward Jupiter. This process continued, with each new moon forming in the thinned-out material left behind by the previous one.

- Orbital Resonance: This sequential formation and inward migration is what’s thought to have led to the striking orbital resonance of Io, Europa, and Ganymede. For every four orbits completed by Io, Europa completes two, and Ganymede completes one. This gravitational “tug-of-war” is responsible for the intense tidal heating that drives the geological activity on these moons, particularly the volcanism on Io.

The differing compositions of the Galilean moons—rocky Io and Europa, and icy Ganymede and Callisto—are explained by this formation model. The inner regions of the circumplanetary disk were hotter due to their proximity to Jupiter, causing volatile materials like water to vaporize. This meant that the inner moons, Io and Europa, formed with more rock and less ice. The outer moons, Ganymede and Callisto, formed in cooler regions where water ice could condense, leading to their icy composition.

We already know a decent amount about how planets form, but moon formation is another process entirely, and one we’re not as familiar with. Scientists think they understand how the most important Moon in our solar system (our own) formed, but its violent birth is not the norm, and can’t explain larger moon systems like the Galilean moons around Jupiter. A new book chapter (which was also released as a pre-print paper) from Yuhito Shibaike and Yann Alibert from the University of Bern discusses the differing ideas surrounding the formation of large moon systems, especially the Galileans, and how we might someday be able to differentiate them.

The Galilean moons form what is known as the circum-Jovian disc (CJD), and analogue of the circum-stellar disc (CSD) that surrounds the Sun, but instead has Jupiter at its center. The other 93+ non-Galilean moons around Jupiter also define the CJD, but their creation might be different due to the size differentials.

According to the paper, there are three main differences between the formation of planets and the formation of moons. Moon formation happens on a much faster time scale – around 10-100 times faster than planet formation. The system itself is also always gaining additional material from the CSD and losing it to whatever is at the center of the disk, which in the CJD’s case is Jupiter. And finally, there aren’t nearly as many examples of systems with multiple large moons as there are planetary systems, at least since the discovery of exoplanets 30 years ago. Jupiter and Saturn remain our only examples of large moon systems, and it will be awhile before any multi-exo-moon system will be found.

What is Jupiter galileans moon structure and features

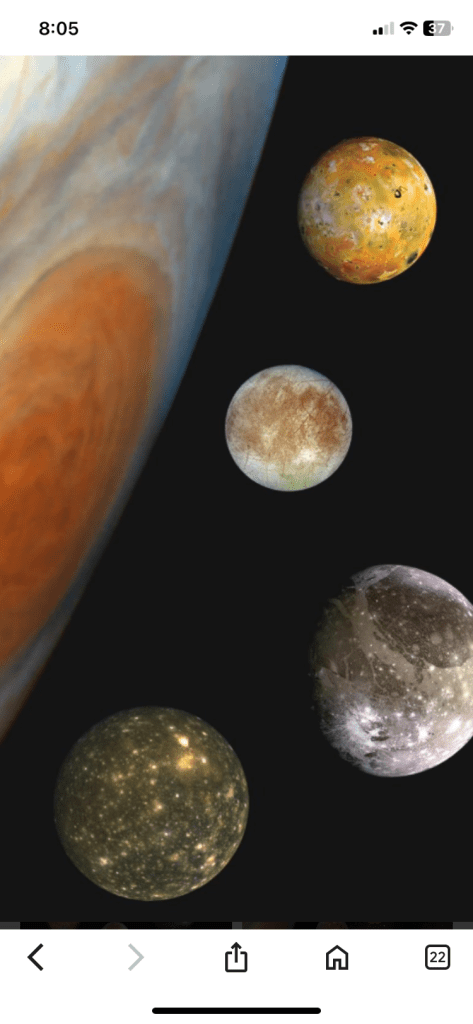

Jupiter’s Galilean moons—Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto—are four unique worlds, each with a distinct structure and features shaped by their distance from Jupiter.

Io: The Volcanic Moon

Io is the innermost of the Galilean moons and the most volcanically active body in our solar system. Its surface is constantly being reshaped by eruptions, giving it a striking patchwork of reds, yellows, and whites from sulfur compounds and silicate rock. Io’s intense volcanism is caused by powerful tidal heating, where Jupiter’s gravity and the gravitational pull of Europa and Ganymede stretch and squeeze the moon’s interior. This constant deformation generates immense heat.

- Structure: Io has a differentiated interior with a large, partially molten iron or iron-sulfide core, a silicate mantle, and a thin crust. The interior may contain a “magma ocean” which decouples the crust from the mantle.

- Surface Features: Over 400 active volcanoes, lava flows, and mountains taller than Mount Everest. The lack of impact craters indicates its surface is very young and is constantly being resurfaced by volcanic activity.

Europa: The Icy Ocean Moon

Europa’s surface is a pristine, white-to-tan canvas of water ice crisscrossed by a network of cracks and ridges. It has very few impact craters, suggesting a geologically young surface. The most compelling feature of Europa is the strong evidence for a vast, global ocean of salty liquid water beneath its icy crust, which could be twice the volume of all of Earth’s oceans. - Structure: Europa has a layered structure: a metallic core, a rocky mantle, and a water layer. This water layer is composed of a deep liquid ocean beneath a thick crust of ice. The thickness of the ice shell is still debated, but it’s estimated to be about 10–15 miles (15–25 km) thick.

- Surface Features: A smooth surface with very few large craters. The most prominent features are the chaotic terrains and long linear fractures, or “lineae,” which are believed to be caused by tidal stresses from Jupiter, flexing the icy crust over the subsurface ocean.

Ganymede: The Magnetic Moon

Ganymede is the largest moon in the solar system, even bigger than the planet Mercury. It’s the only moon known to generate its own magnetic field, likely from a convecting liquid iron core. Its surface is a mix of two distinct types of terrain: older, dark, heavily cratered regions and younger, brighter terrain marked by grooves and ridges. - Structure: Like the other Galilean moons, Ganymede is fully differentiated. It has a liquid iron core, a silicate mantle, and an outer shell composed of ice and rock. Like Europa, Ganymede is also believed to have a subsurface ocean, but it’s located between layers of ice, possibly making it less accessible.

- Surface Features: The surface is defined by its dichotomy of light and dark terrain. The light regions show signs of tectonic activity, with complex patterns of grooves and ridges, while the dark regions are heavily cratered, reflecting their ancient age.

Callisto: The Ancient Moon

Callisto is the most heavily cratered object in the solar system and has the oldest and darkest surface of the Galilean moons. Its appearance suggests it’s a “fossil world” with very little geological activity since its formation. Its distance from Jupiter means it’s not affected by the same intense tidal heating as its inner siblings. - Structure: Unlike the other Galilean moons, Callisto is not fully differentiated. Its interior is a mixture of rock and ice, with no distinct core. However, there is evidence that a salty subsurface ocean may exist below its icy crust, likely at a great depth.

- Surface Features: Its surface is saturated with impact craters, many with concentric rings, a testament to billions of years of bombardment by asteroids and comets. The lack of resurfacing events like volcanism or tectonic activity means that these craters have been preserved over billions of years.

Please like subscribe comment your precious comment on universe discoveries

Full article source google

https://www.buymeacoffee.com/Satyam55

https://www.amazon.in/b?_encoding=UTF8&tag=555101-21&link

https://youtube.com/shorts/uBICBl3fq88?si=Dua2Zmr_dkdtUzWU

Click on the above link to see Jupiter galilean moons video

That’s a wonderfully clear and engaging explanation 🌌👏. You’ve beautifully unraveled the mystery of how Jupiter’s Galilean moons might have been born from a circumplanetary disk. I especially appreciate how you highlighted the step-by-step journey—from dust grains to satellitesimals, then to moon embryos, and finally to the harmonious orbital resonance that keeps them dancing in rhythm.

LikeLike

🙏🌹

Aum Shanti

LikeLike

Sir thanks for reading and appreciating 🎸your words means a lot to me , yes these moons of Jupiter are very interesting 🎸

LikeLike

More awesome information, that’s why I love your site.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks renell its your kindness 🙏

LikeLiked by 1 person

But it’s true

LikeLike